PLANES of FAME - General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark

Update: 2022/04/03 by Robert Kysela / CHK6

Few aircraft have generated as much controversy during their careers as the General Dynamics F-111 AARDVARK. This controversy began long before the types maiden flight on 21 December 1964, and only to reappear in 1969 when it was grounded for over seven months following a catastrophic accident. Delivery of the F-111 to its sole export customer, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), was preceded by a lengthy delay of almost ten years, while another problem was its astronomically high development and manufacturing costs. As such, while the F-One-Eleven can look back on quite an eventful past, the plus side was the fact that this fascinating machine later went on to become a tremendous success.

The F-111 incorporated many technical features making it one of the most effective tactical combat aircraft of our time. The success of this machine was highlighted by the fact that the RAAF retired the PIG (as the F-111 is affectionately known in Australia) as late as 2010.

In order to save costs, the then US Secretary of Defence, Robert McNamara, favored a joint development program that would address both NAVY and AIR FORCE requirements.

R. Kysela

The specifications for the new fighter, initially entitled TFX (Tactical Fighter, Experimental), later to be renamed F-111, were originally based on a United States Air Force (USAF) requirement calling for a fighter incorporating a variable geometry wing, high fuel capacity, the ability to deliver a tactical nuclear weapon at low level, supersonic speeds into enemy territory. The ability to take off and land on unpaved runways was also an important requirement under Specific Operational Requirement SOR-183. The latter was however a double-edged sword as the use of massive low set undercarriage with huge low-pressure tires came with the risk of Foregin Object or Debris (FOD) being ingested into the air intakes. At about the same time, development of the US NAVY Douglas F-6D Missileer was put on hold by the newly elected Kennedy administration as the F-6D was seen as a technological step backwards when compared to the newer McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II. In order to save costs, the then US Secretary of Defence, Robert McNamara, favored a joint development program that would address both NAVY and AIR FORCE requirements. Because of their fundamental differences between conceptual ideas of operational requirements, it was almost impossible for the two branches to reach any agreement regarding key points of the new aeroplane. As such, it was impossible to reach a compromise on what would effectively produce a “Jack of all trades” for both services

No fewer than four design competitions were conducted, all of which were won by Boeing. A scandal arose when McNamara awarded the contract to build the new fighter to the General Dynamics and Grumman companies, despite Boeing being the clear winner. The NAVY variant, the F-111B made its maiden flight on 18 May 1965 and although the F-111B passed the carrier tests without any major difficulties, it proved to be too heavy and above all too expensive, which resulted in the program being cancelled in 1968. This however, allowed for the US NAVY to follow its own course regarding the new fighter with US Congress giving approval for the VFX program, from which the Grumman F-14 Tomcat emerged. Much of the new technology and lessons leant from the Missileer and F-111 projects were incorporated into the Tomcat, including the AWG-9/AIM-54 Phoenix weapon system, along with variable geometry wings and afterburning turbo-fan engines (Pratt & Whitney TF-30).

Highly controversial, despite considerable advantages over conventional ejection seats, was the crew escape module.

R. Kysela

The F-111 represented a quantum technological leap in many respects. It was the first operational fighter to employ variable-geometry wings, while the use of turbofan engines with afterburners provided considerable power and comparatively low fuel consumption. Terrain-following radar (TFR) was used for the first time, and its sophisticated multi-mode radar system had the ability to track up to 24 targets simultaneously. Highly controversial, despite considerable advantages over conventional ejection seats, was the crew escape module. The effectiveness of this system was soundly demonstrated when the crew of an F-111D lost control of their aircraft at Mach 2. Following a safe ejection, both officers were able to resume flying duties the very next day. A process that would have been simply unimaginable if conventional ejection seats were used.

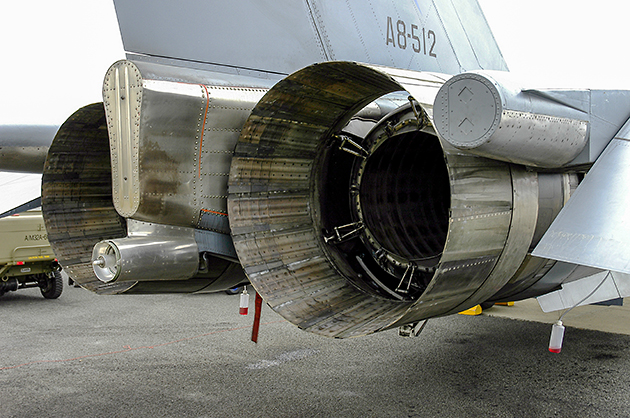

One of the weak points of the F-111 were its Pratt & Whitney TF30-P-3 engines, which often tended to stall (compressor stall). Attempts were made to overcome this problem by modifying, amongst other things, the air intakes, however this was only partially successful. Although the Aardvark was designed as an all-weather fighter, engine stalls in high humidity (heavy rain) was also a significant issue. Additionally, its complex radar system caused ongoing problems, particularly in its early years of development.

The main landing gear was also a cause for concern. Although it was extremely robust, its relatively low set design lacked adequate clearance between the air intakes and the ground which meant the F-111 could only take off from well cleaned runways. The danger of FOD being ingested into the turbines meant that take-off and landing on unpaved runways was not possible, even though the F-111 was originally designed for this purpose. Another important weak point that required remediation was the structural design of the articulated joint of the wing pivots. This design flaw led to the fatal crash of one aircraft on 22 December 1969.

Despite all of these shortcomings, the F-111 can however look back on a very successful career. The F-111 flew its first combat missions over Vietnam in 1967 with several aircraft being lost due to technical problems, although the loss of most of these aircraft was later attributed to pilot error. After these problems were mostly rectified the South-East Asia deployments were largely seen as being very successful. In more than 4,000 missions, only six aircraft were lost – a loss rate far below that of other combat aircraft at the time.

On 14 April 1986, 24 F-111F aircraft of the USAF 48th TFW (Tactical Fighter Wing) from RAF Lakenheath (UK) flew a targeted attack on the Libyan capital of Tripoli. This was the first ever successful use of the Ford AN/AVQ-26 Pave Tack Electro-Optical Target Marking System. Further successful military missions took place during the 1991 Gulf War where more than 2,500 missions were flown resulting in 2,203 targets being hit including 920 tanks, 245 aircraft shelters, 12 bridges and 113 bunker positions (according to official US DoD data). Not a single F-111 was lost.

The RAVEN was intended as a replacement for the obsolete Douglas EB-66 in the EW/ECM role

R. Kysela

By the mid 1990’s, most F-111’s within the USAF were retired from service with only one version, the EF-111A RAVEN Electronic Warfare/Electronic Countermeasures (EW/ECM) aircraft, remaining in USAF service. The RAVEN was intended as a replacement for the obsolete Douglas EB-66 in the EW/ECM role. The EF-111A received an AN/ALQ-99E jamming radar as well as other various EW/ECM equipment including a more powerful generator, providing a whopping 90 kVA of output (the original generator produced: 60 kVA), to power the new electronic systems. The new electronic warfare equipment, which included an AN/ALQ-137 jammer, AN/ALR-62 radar warning system, and an AN/ALR-23 radar wave jamming receiver, increased the empty weight of the aircraft to more than 23t, but because the EW/ECM variant did not carry any offensive weapons, its take-off weight was more than 5t lighter than a fully combat loaded F-111A. The prototype of the EF-111A made its maiden flight on 17 May 1977 with a total of 42 EF-111A aircraft being converted from the existing USAF fleet. The RAVEN was the last version of the F-111 to be used by the USAF and was decommissioned and mothballed in 1998 as a result of cost-cutting measures (Davis-Monthan AFB).

One disadvantage of this complex weapon system was its high price tag and was also the main reason why the F -111 was not a great export success. Apart from the United States Air Force, only the Royal Australian Air Force operated this modern capable platform. An order from the British Ministry of Defence for 46 F-111K fighter-bombers and four TF-111K trainers was cancelled in 1968 due to the high price tag (the official reason). In Royal Air Force (RAF) service, the F-111 would have served as a replacement for the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) TSR.2, which sadly was cancelled. To replace its aging fleet of English Electric Canberra bombers, the decision was made in October 1963 to purchase a total of 24 F-111 aircraft for the RAAF with delivery expected in 1968, however it not until June 1973, almost ten years later, that the first F-111C entered Australian service. During this time the RAAF leased a fleet of 24 McDonnell Douglas F-4E Phantom II aircraft to address the extant capability gap. Four of the F-111C received were converted to RF-111C reconnaissance aircraft, while another four ex-USAF F-111A’s were purchased to backfill the converted C model aircraft.

All Australian F-111’s were operated by No.1 and No.6 Squadrons of 82 Wing - Air Combat Group (ACG) based at RAAF base Amberley Queensland

R. Kysela

Upgrades to the RAAF F-111 fleet started as early as 1985. The Pave Tack laser designating system was retrospectively fitted as well as other modern weapon systems such as the AGM-84 Harpoon Anti-Ship Missile (ASM), the AGM-88 High Speed Anti-Radiation Missile (HARM) and the Australian developed Karinga cluster munitions. An additional 15 former USAF F-111G (ex-FB-111A) aircraft were acquired by the RAAF in 1993 and beginning in the early 1990’s, all Australian Aardvarks underwent a series of extensive avionics upgrades under the F-111 Avionics Update Program (AUP). All Australian F-111’s were operated by No.1 and No.6 Squadrons of 82 Wing – Air Combat Group (ACG) based at RAAF base Amberley Queensland. One F-111C was assigned to the Aircraft Research and Development Unit (ARDU), based at RAAF base Edinburgh South Australia, where it was used primarily for weapons testing.

With the F-111 the RAAF possessed a powerful strike aircraft which, with its long range, high speed and the ability to deliver a considerable weapons load at very low-level with pinpoint accuracy, truly dominated the entire Pacific region. While the F-111 never saw combat in RAAF service, during the 1999 conflict over the independence of East Timor, a number of F-111’s were deployed to RAAF base Tindal in the Northern Territory as a preemptive measure to counter any attempt by the Indonesian military to regain control of the small island nation. Overall, the RAAF was very satisfied with the F-111, even though maintenance costs per flying hour were very high and its utilisation of older analogue technology became more demanding. For this reason, the RAAF began to phase out its F-111G fleet as early as 2007, while the last F-111C’s was officially decommissioned on 3 December 2010.

To replace the F-111, the Australian government procured 24 Boeing F/A-18F Super Hornets, with the first five aircraft arriving in Australia at the end of March 2010. Even though the F/A-18F is a much more modern platform, the Super Hornet still could not replace the Pig in many respects, and if so, only somewhat poorly. The Super Hornet has neither the range of the F-111 (just half that of the Aardvark), nor is it capable of accurately delivering a comparative weapons load at very low level, at supersonic speeds in all weather. An interesting feature of the F-111 is that the fuel dump valve is located between its two engine exhausts. Released fuel can be ignited by the two engine exhausts (usually in afterburner) producing the famous F-111 “Dump and Burn” an incredible sight that is always popular at Australian airshows, this spectacular sight is however not without risk. The USAF had strictly banned the practice as one incident almost turned an Aardvark into a grilled suckling pig.

Robert Kysela & Rob Hynes / CHK6